April 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of a Salmo mine accident and resulting acts of extraordinary heroism by 12 men, who were awarded the Carnegie Medal in 1972.

It is likely that Friday, April 18, 1969, began as any other day at the Jersey Mine Canex in Salmo, B.C. The morning hours passed fairly routinely for Gilbert Mosses, a 53-year-old mine mucker boss, who supervised men responsible for clearing the mine of debris from detonated blasting.

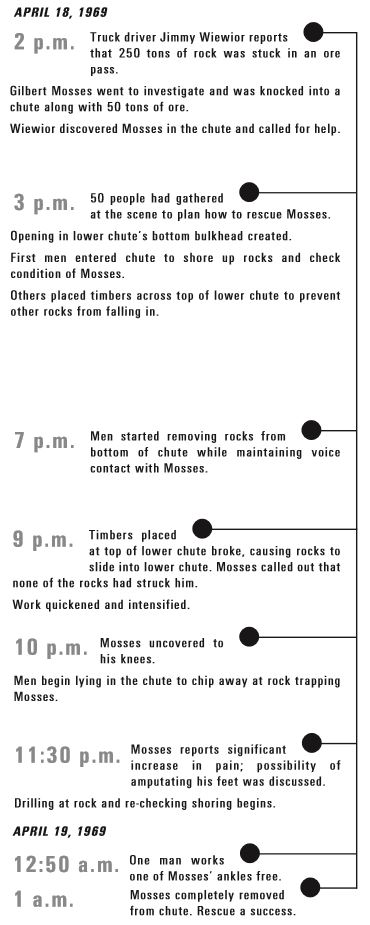

At 2 p.m. truck driver Jimmy Wiewior reported that 250 tons of lead and zinc rock was stuck in an ore pass that used two chutes – a 70-foot-long upper chute and a lower chute, 22 feet long, 8 feet wide, and set at a 30 degree angle – to transport debris from one area inside the mine to a lower area where it was then loaded into trucks for removal from the site.

In response, Mosses traveled through a tunnel to reach the junction of the two chutes, an area of open space several feet tall, while Wiewior left the area.

While Mosses attempted to dislodge the rock stuck in the upper chute using bulldozing and blasting, 50 tons of ore broke free and knocked Mosses into the lower chute head-first. Mosses came to rest lying on his back. His head was about 8 feet from the bottom of the chute, and his feet were positioned farther up the chute. Rocks – ranging in size from particles to 3 feet in diameter – buried the majority of his body. Only his head, neck, and right arm were free.

Wiewior returned to the area and positioned his truck under the lower chute. He told mine bosses later that since he did not see Mosses, he assumed that the chutes had been repaired.

He climbed onto the chute platform to operate the controls, but he heard Mosses yelling from inside the chute. Wiewior ran 800 feet to a telephone and called mine shift boss Andrew Burgess, 63, who then notified others.

Within an hour, 50 people had gathered at the scene of the accident, including 38-year-old shift boss Carl A. Shelrud, 33-year-old mine manager Edward A. Lawrence, 33-year-old first-aid man Joseph Laurent Heroux, miners Edward M. Gladu, 36; Brian D. Martin, 21; Alphonce F. Grotkowski, 33; John J. Voykin, 37; Wayne R. Ritter, 32; Graham D. Bingham, 30; and 24-year-old nipper Dale R. Burgess. After inspection, it was decided it would be nearly impossible to remove the 50 tons of broken ore from the top of the chute containing Mosses. This left the rescue team in the dangerous position of approaching

the trapped man from the bottom of the chute without disturbing the precariously positioned rocks above or below Mosses.

Several 1-foot-thick timbers made up a bulkhead at the bottom of the chute that was opened and closed hydraulically. With only their headlamps to illuminate the area, men used a chainsaw to cut through two timbers, until the saw broke on a large rock behind a timber. By then a 2-by-3-foot opening had been carved out of the bulkhead, and others worked to remove rocks at the opening. For the first time, the men were able to see Mosses.

The rescue team expressed worry about the tons of rock shifting and crushing Mosses as well as any rescuers inside the chute. Nevertheless, Shelrud and Andrew Burgess entered the opening and crawled to Mosses to check his condition. En route, they positioned wood against any rocks that appeared to be key in keeping the other rocks in place. The pair exited the chute and reported that although his breathing was labored, Mosses was able to converse coherently. Then Lawrence, mine manager, entered the chute with Andrew Burgess to observe the situation. He shared that he felt that the rocks were not very secure and expressed his concern for Mosses’ condition.

Meanwhile, a 46-year-old local physician, Ian F. Stewart, had arrived on the scene. Stewart, along with first-aid attendant Heroux, entered the chute to examine Mosses. Stewart stated that although he was not critically injured, keeping him in that position for a prolonged period of time could result in fatal injury. Heroux re-entered the chute and fitted Mosses with an oxygen inhalator, which he could operate with his free hand.

While the men inside the lower chute assessed Mosses’s condition, others went to the top of the chute and placed timbers across its opening to prevent the 200 tons of remaining ore in the upper chute from falling into the lower chute.

By 7 p.m., five hours after the accident, men outside the bottom of the chute started to use scaling bars to pull rocks through the opening of the bulkhead and into a truck, hoping to gain access to Mosses.

According to the Commission’s investigative report, while the men removed rocks from the chute’s lower end, “the rock movement was generally controlled but occasionally rocks rolled down at high speed and caused concern.”

Although they maintained contact with Mosses by voice and he reported that he felt no major shifting of the rocks nearest him, he did begin to feel pain.

At 9 p.m., the timbers that were placed at the top of the lower chute broke and rocks from the upper chute slid into the figuring one.

“There was a grave concern that Mosses may have been crushed by the debris,” the report stated, but “after several minutes, Mosses called out that none of the rocks had struck him.”

The men worked quickly then, entering the chute two at a time to remove rocks and reach Mosses. Large timbers were passed into the chute to shore up rocks that could fall on Mosses and the volunteers working tirelessly to free him. Each team only stayed inside the chute for 10 minutes to minimize their chances of becoming trapped themselves.

By 10 p.m. Mosses had been uncovered to his knees. There, the men found a rock that could not be moved without disturbing the shoring of a larger rock just beyond Mosses. Several men took turns lying prone in a crawl space while chipping away at the rock attempting to free Mosses’ feet.

Near 11:30 p.m., Mosses reported significant increase in pain, and the possibility of amputating Mosses feet as the only solution was discussed. Stewart reported that because of the confinement any amputation would have to be of the legs instead. The rescue team pleaded for more time before such a drastic measure was taken, the report stated.

After seeing little results with the continuation of chipping, a small drill was tried, but the men worried its vibrations would cause the remaining ore precariously positioned above Mosses to come crashing down.

Tension was high as the men continued to work in shifts, drilling, then checking and resetting the shoring that had been placed around the rocks above Mosses. This went on until 12:50 a.m. when Shelrud worked one of Mosses’s ankles free.

Nearly 10 minutes later, he was completely removed from the chute, placed on a stretcher, and taken to a waiting ambulance. He was detained at the hospital for several months for treatment of shock, internal bleeding, and fractured ribs. He returned to work five months later.

Nearly 10 minutes later, he was completely removed from the chute, placed on a stretcher, and taken to a waiting ambulance. He was detained at the hospital for several months for treatment of shock, internal bleeding, and fractured ribs. He returned to work five months later.

A report by the mine company, Canadian Exploration Limited, stated that “this difficult and hazardous rescue was successful because of the efforts of many people,” including those involved in an indirect way:

“In all about 50 people were available for innumerable ‘errands,’ cutting timbers, packing timber, packing drill steel and pipe, driving trucks. Guarding the top of the ore pass, obtaining engineering drawings, maintaining services such as telephone, compressed air, and power, and operating oxy-acetylene torches. Food and coffee was provided by a number of the ladies who live at the Mine Townsite. The R.C.M.P. at Salmo delivered spare oxygen bottles to the mine when the mine supply ran low. Many volunteers were available from the afternoon shift crew if we felt we needed them to replace anyone tiring form the long rescue,” the report stated.

But it was 12 men who took on the extraordinary risk of entering the chute, where the rocks could settle and crush them. Shelrud was the first man to venture into the chute and continually returned to dig and drill throughout the rescue. Andrew Burgess entered next. The mine company’s report stated that his “ability to lead and work with men was invaluable.”

M. E. Crayston, a safety engineer for Canadian Exploration Limited, estimated that Shelrud and Andrew Burgess spent a total of three hours inside the chute.

He also estimated that miners Bingham, Gladu, Grotkowski, Martin, Ritter, and Voykin spent a total of two hours inside the chute. They, along with Dale Burgess, who spent one hour inside the chute, were credited in the mine company’s accident report.

“They were all at risk of serious injury if a false move was made and it is to their credit that they all displayed exceptional coolness while working under extremely difficult and hazardous conditions,” the report stated.

Finally, while Stewart and Heroux spent the least amount of time in the mine – 30 minutes – their participation in the rescue was integral and “required unusual courage because of [their] inexperience in an underground environment.” They had not been trained in mine safety.

On May 3, 1972, the 12 men who entered the chute were awarded the Carnegie Medal for their heroism.

— Lauryn Maykovich, intern