Two men attempt to pull coworker from oxygen-deficient, toxic gas-filled water box

On the morning of Friday, October 19, 1984, 50-year-old Lloyd Hansen, senior control operator from Watsonville, California, was working at an inoperative surface condensing unit at a Pacific Gas and Electric Company fossil-fuel power plant in Moss Landing, California, adjacent to the Monterey Bay.

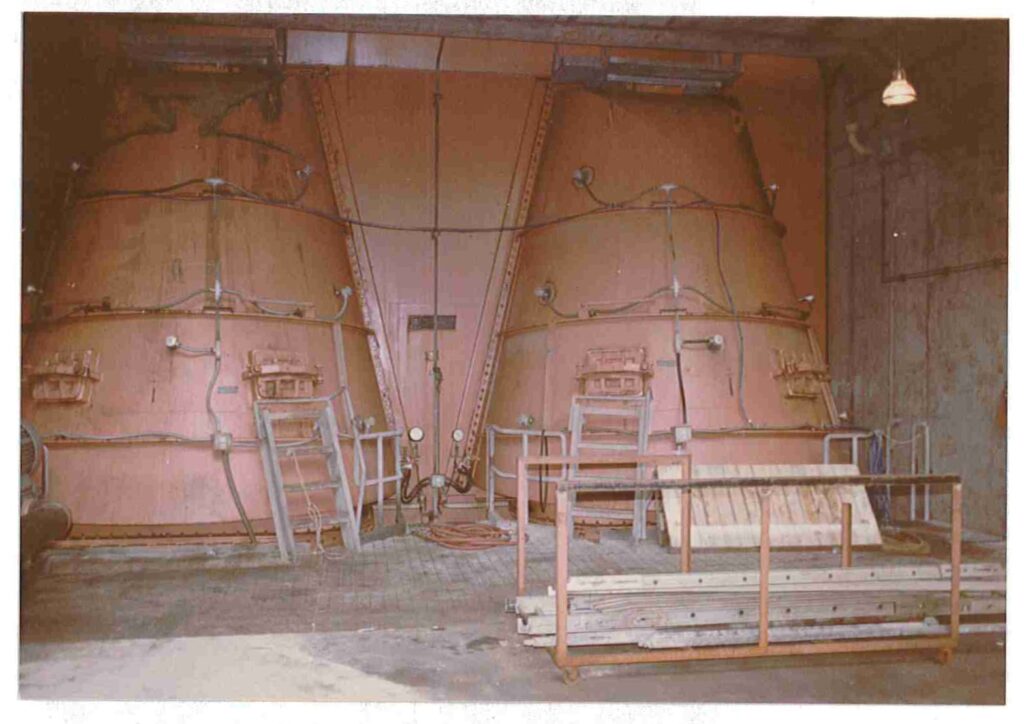

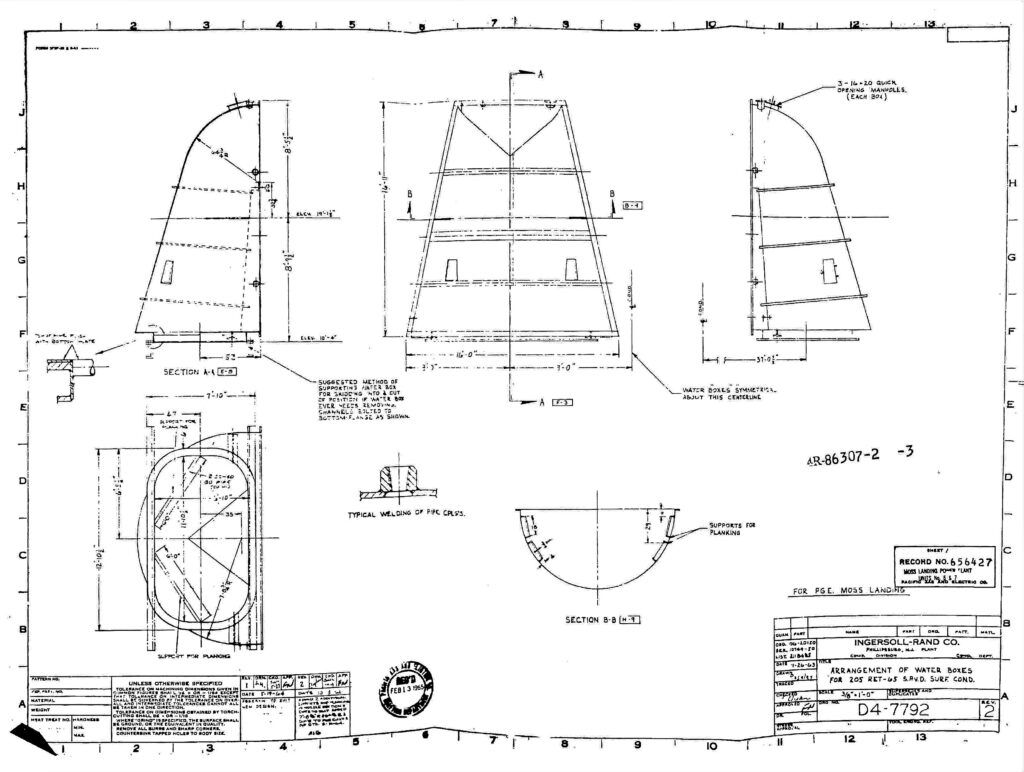

The power plant used steam turbines to generate electricity, using the surface condenser to capture steam exhausted from the turbine and then cool it and condense it for reuse. The condenser pumped sea water, transported to the plant via an underground pipe, through tubes inside a 21-foot-high, semi-circular, steel water box where the steam exhausted. The cold water cooled the steam back into liquid, collected at the bottom of the box.

The condenser was 15 feet wide at its base, tapering up. A 9-foot-wide vertical tunnel under the box contained still seawater that had sat since the broken unit was shut down 38 days prior. As employees worked to fix the condenser, a temporary floor was installed inside the water box, leaving a 3-foot-wide opening at the base of the unit to the tunnel. Workers could enter the water box through either of two small hatches.

The surface of the seawater was about 14 feet below the temporary floor, where decaying marine life floated. Dangerous concentration of dimethyl sulfide, methyl mercaptain, and hydrogen sulfide gases had built up in the tunnel, though the unit had been vented a number of times in the previous week after plant workers working to drain the tunnel detected a strong smell.

On the morning of the accident, Hansen called a 23-year-old auxiliary operator and asked him to meet him at the water box.

In the meantime, Hansen entered the water box through one of the 20- by 16-inch hatches. According to a state occupational safety and health division report, several employees saw Hansen inside the water box adjusting the submersible pump intended to drain the sea water from the tunnel.

The auxiliary operator and Rex A. Lewis, a 30-year-old operating foreman from Watsonville, California, approached the scene but they could not find Hansen. His gloves, hard hat, and wrench lay ominously outside the hatch.

Lewis and the operator actively searched for Hansen, looking through the hatches and down through the temporary floor. The submersible pump had been placed in the water, which was creating turbulence. When it was turned off, the water calmed, and Hansen was floating face-down on the water’s surface.

“Help!” called Lewis and the operator.

Michael DeWitt Puckett, 31, mechanic from Fresno, California, and another man ran to the water box.

Other coworkers rushed over with rope for Lewis and the operator to tie around themselves. Lewis and the operator entered the water box.

The operator, getting dizzy, cautioned Lewis to flee the water box, then exited to get more assistance.

From inside, Lewis instructed the men outside the box to lower him by the rope into the water tunnel so he could attempt to retrieve Hansen. Lewis reached the water’s surface and placed a hand on Hansen’s back to steady his descent.

Puckett then saw Lewis go limp.

“Pull him up!” Puckett shouted.

The workers pulled on the rope to raise Lewis, but he became stuck on the temporary flooring inside the water box and could not be lifted higher.

Without a breathing device or rope, Puckett immediately entered the water box. Suspecting the presence of methane gas in the unit’s atmosphere, he tried to breathe as little as possible as he reached toward Lewis through the opening in the floor.

Puckett grasped Lewis under his arms and pulled him up into the water box. As he lifted Lewis to one of the hatches, Puckett began feeling dizzy, and went to the other hatch to get a breath of fresh air.

Meanwhile, those outside the water box struggled to remove Lewis from the opening. Catching his breath, Puckett returned to push Lewis through the access point. Lewis had stopped breathing several times and needed mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. In the interim, Hansen remained inside the water box.

After Lewis had been pulled to safety and revived, Puckett left the water box to fetch a self-contained breathing apparatus that had a small oxygen tank before climbing back through the hatch and affixing the device to his face.

He clambered to secure Hansen, twice running out of oxygen and needing to get a new tank, and once entering the water, only ceasing his efforts once fire fighters arrived.

It took firefighters two hours to retrieve Hansen. He was taken to a hospital and attempts were made to revive him, but were ultimately unsuccessful.

Lewis, Puckett, and the auxiliary operator were the only three employees who had fully entered the water box to effect a rescue, but a total of 31 employees underwent medical surveillance for exposure to the toxic gases inside the tunnel.

At the hospital, Lewis was admitted to the intensive care unit where he was treated for methane gas intoxication, lack of oxygen to the brain, and possible aspiration of water. He regained consciousness about five hours later. He was released the next day and made a full recovery.

During a conversation with Dooley, Lewis said that when he woke up in the hospital he thought his alarm had gone off and he was late for work.

Unfortunately, Puckett suffered more long term effects from his participation in the rescue effort. After receiving oxygen at the power plant, he experienced uncontrolled vomiting for six months. His doctor attributed this to Puckett inhaling one of the gases present in the water tank.

During his extensive research, Hero Fund case investigator Jeff Dooley gathered eyewitness accounts of the actions of Lewis and Puckett, consulted the plant manager, reviewed a lengthy and wide-ranging company report, and accessed third-party summaries of the accident to build a solid case for awarding Puckett and Lewis for their heroic deeds.

Dooley learned from the plant manager that Hansen had violated plant safety procedures in trying to drain the tunnel, and that neither rescuer was responsible for Hansen’s safety.

However, an independent investigation performed by state occupational safety and health division did find the company at-large responsible. The power company “had been operating for 30 years and should have known that poison gases or lack of oxygen could have existed in their confined spaces, and appropriate measures should have been taken to prevent this type of accident,” the report concluded.

In addition to interviewing the two rescuers, Dooley questioned two other employee eyewitnesses to the rescues.

Lewis and Puckett were awarded the Carnegie Medal on December 16, 1986, and were granted $2,500.

— Abby Brady, operations and outreach assistant/archivist