On Feb. 25, 1963, off the coast of Grand Manan Island in Canada’s New Brunswick province, Floyd D. Jones and his brother were fishing in a 15-foot motorboat when the craft’s carburetor froze, disabling the boat’s engine. The brothers drifted in the Bay of Fundy amid rough seas for 12 hours. The wind steadily increased to upward of 70 m.p.h. whipping across the bay. A large swell picked up the boat and deposited it on a small beach at the base of a 200-foot, near-vertical cliff. Jagged, eroding rocks, patches of ice, and shrubs dotted the cliff face. Tide was rising, inundating the small beach.

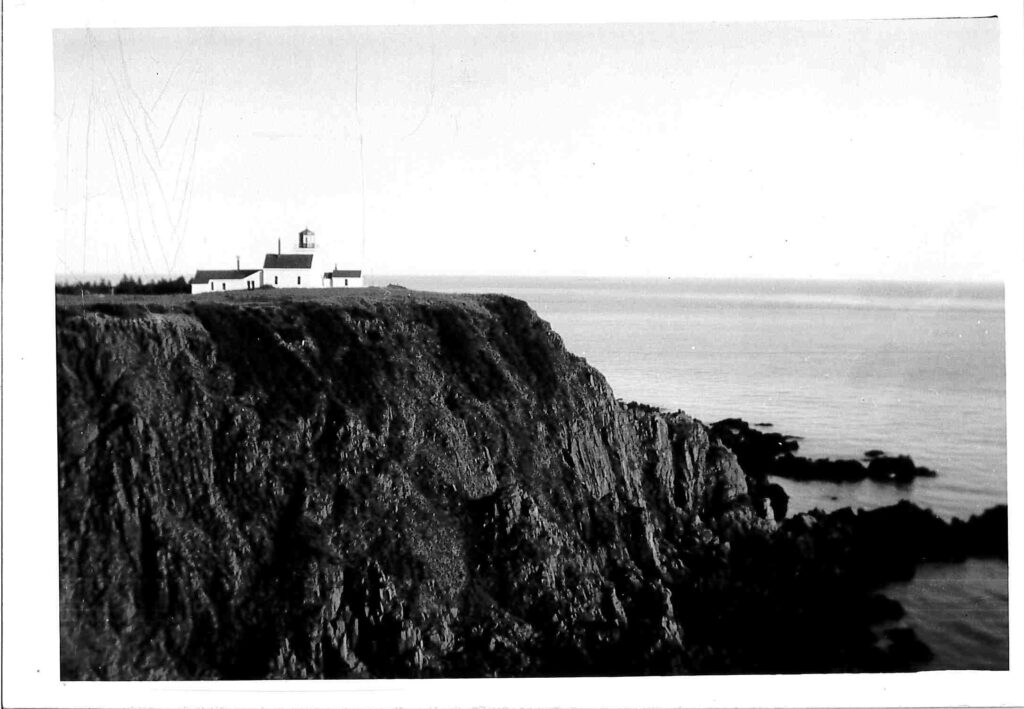

Fearing they would freeze to death, Jones and his brother found foot- and hand- holds and ascended the rocky coast. Jones climbed 20 feet to a small ledge. With waves pounding the cove below, Jones, soaking wet and huddled in a hollow on the cliffside, cycled in and out of consciousness as the frigid, 18-degree night numbed his legs; he could no longer climb. For the next three hours, Jones’s brother continued the remaining 180 feet to the top of the cliff and then trekked .75 miles through a foot of snow to the Southwest Head Light House, where he informed the lighthouse keeper that his brother was stranded in a niche on the cliffside.

The lighthouse keeper telephoned a number of men, including Vernon P. Bagley, a game warden for the provincial government who was well acquainted with the cliff and surrounding area’s dangers, and Sidney A. Guptill, an assistant lighthouse keeper. A rescue party of about 15 men carrying several ropes followed the tracks set by Jones’s brother to the edge of the cliff.

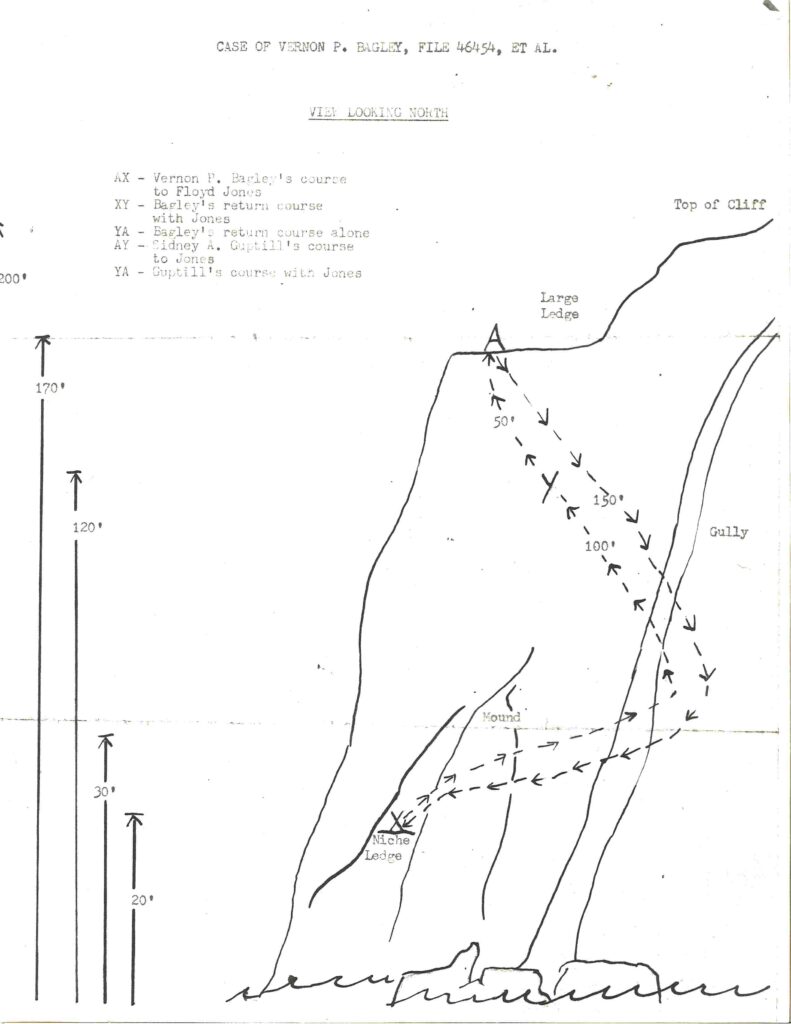

From a ledge near the top of the cliff, Bagley – who was attached to a rope 200 feet long — and Guptill – whose rope measured 100 feet — descended the cliffside. After 5 feet, rocks and dirt loosened from the cliff and tumbled into the frothing waters below. The two men returned to the ledge to regroup. Assuming that no man could survive the conditions, the group concluded that further rescue attempts were too risky, when they could retrieve Jones’s body in the daylight after the weather improved.

But a lull in the wind allowed Jones’s faint moans to be heard, and, knowing that Jones was alive, Bagley descended the cliff face again. The others held one end of Bagley’s rope. He quickly descended 15 feet and disappeared from sight. Bagley crossed a small ravine in the side of the cliff, 4 feet wide and 3 feet deep, and descended another 150 feet. He shouted for Jones, who provided a weak response. Following his voice, Bagley crossed the ravine again, searching the area with a flashlight. Finally, he spotted Jones 10 feet below him. He made his way down to Jones on the ledge, which was barely large enough for both of them, about 3 feet square.

Bagley put mittens on Jones and instructed him to grab the rope. Bagley turned to face the cliff and, with Jones clinging to the rope behind him, towed Jones up the slope retracing his steps as the men above drew the rope taut. At one point, Bagley told Hero Fund Investigator Joseph E. La Roca, that he noticed the rope was caught on an outcropping above them. He told La Roca that he feared the rope would slip from the rock, causing the men above to suddenly bear Bagley’s and Jones’s full weight and cause them to drop the rope. All he could do, however, was to keep climbing.

The duo had ascended 50 feet when Jones said he could no longer hold to the rope and begged Bagley to tie it around him. Bagley untied the rope from himself and tied it around Jones. Then

holding to the rope below Jones, Bagley continued upward, pushing Jones, who was in and out of consciousness, ahead of him. They continued laboriously like this – Bagley pushing the full weight of Jones up the cliff and then, holding to the rope for dear life, scrambling up behind him — for

another 60 feet, until Bagley could not continue. He told Jones he would return to the top of the cliff, rest, and procure another rope for himself. Bagley climbed hand over hand using the rope attached to Jones to the cliff’s ledge, arriving 90 minutes after he began his descent. Exhausted, he informed the rest of the men of the situation. Co-rescuer Guptill, aware of Bagley’s exhaustion and the urgency of Jones’s condition, volunteered to complete the rescue.

With the other rope affixed to his waist, Guptill descended 50 feet, guided by the rope attached to Jones. When Guptill reached Jones, he was unconscious. Guptill positioned himself behind Jones and pushed him up toward the top of the cliff as the other men pulled on both ropes until they

reached the safety of the ledge 30 minutes later. Jones was taken to the hospital. His legs

were so badly frozen that doctors feared they would need amputated, but his condition

improved significantly with treatment, and he was released within three days. According to Investigator La Roca, his legs remained swollen for a month after the incident. Bagley experienced several days of soreness and bouts of nervousness that lasted three months as a result of the incident. Guptill was uninjured.

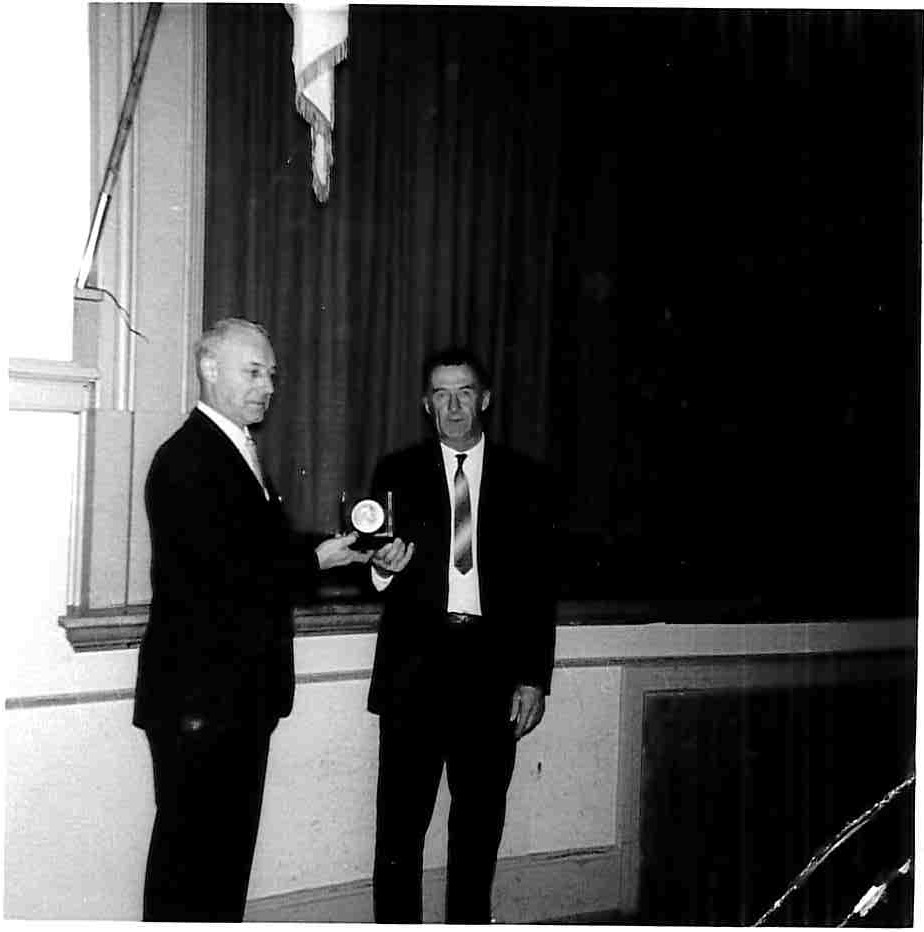

Bagley received the silver Carnegie Medal, Guptill the bronze. They each received $750 from the Commission, which is equivalent to about $7,300 today. Only 617 silver medals were awarded by the Commission before the conclusion of the gold, silver, and bronze medal program in 1980.