Fifty years ago, on the night of July 4, 1969, stormy weather was brewing in the city of Sandusky, Ohio. During this particular electrical storm, 70 m.p.h. gale winds persisted through the night and 11 inches of rain fell. Residents of the city that bordered Lake Erie were busy coping with the heavy rainfall, which caused many basements to flood.

LoRene Limbird, a 66-year old housewife, lived in Perkins Township, a suburb of Sandusky. Around 10 p.m., she asked her neighbor, 29-year-old machine shop technician, Larry E. Smith, to take a look at her basement because she was worried that the freezer was broken. Smith, outfitted in hip waders, moved through the 1 foot of water that covered the basement floor, into a separate fruit room, where the upright freezer was located. He inspected the freezer and believed everything was working properly, but told Limbird that the delayed relay switch might be causing the freezer to struggle when being turned back on.

When he was in the basement, Smith also took a look at the sump pump. It was working at the moment, but wouldn’t be able to handle the extra volume of water coming in. A neighbor and friend, 19-year-old Harry Kresser, was also present. Based on experience dealing with the ill effects of a storm back in 1966, both men suggested Limbird leave the basement window open and allow water to enter. This would alleviate pressure and prevent the concrete block walls from being pushed in by the relentless rain water. Limbird decided against it.

As Smith and Kresser were leaving, Smith told Limbird that if she had any more trouble that night and couldn’t get to the telephone, to turn her front porch light on to signal him.

On their way back to the Smith residence, the men stopped by the home of Larry’s mother-in-law. Firefighters had arrived and were helping salvage articles from the basement.

By now, the weather had worsened and the water outside was deeper. When the duo returned to the Smith residence, Smith’s wife, Vicki, had more news about the state of Limbird’s basement. A neighbor and retired printer, Edward Bender, had called to notify Vicki that more water was entering their neighbor’s home.

As the men readied themselves for another trip to Limbird’s house, Smith decided against driving his truck because he didn’t think it would clear the water. Instead, he and Kresser took a tractor. On the way, they stopped at another neighbor’s house. The family was away so they located a spare key and went down to the basement to check that the sump pump was in working order and place valuable objects on higher surfaces. After the neighborly check, the duo continued on to Limbird’s.

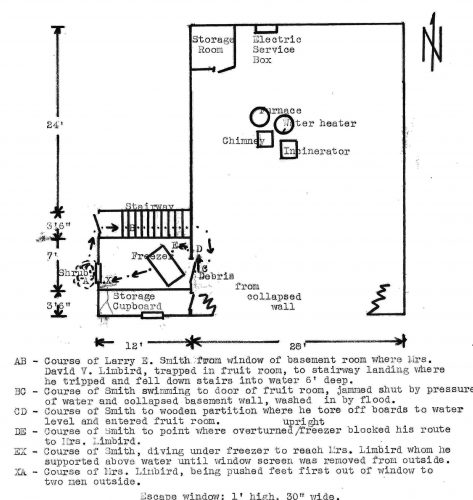

Earlier that evening, Limbird had gone to bed around midnight, but after she realized the severity of the storm, she couldn’t sleep. She put on a dress and stepped into her galosh boots to check the basement. At this point, the water was getting out of control and she wanted to make sure her valuables were okay. As she made her way into the fruit room, Limbird saw that a block about halfway up the concrete wall, was beginning to be pushed into the basement. She stepped over the threshold of the fruit room and the entire south wall collapsed inward. Suddenly, a wave of water, mud, and blocks surged against the opposite wall, closing and jamming the door shut.

In a matter of seconds, the water was level with Limbird’s shoulders. She was a short and stout woman of just over 5 feet. According to the notes of Hero Fund case investigator, F.R. Inglis, she couldn’t swim, float, or tread water.