By Jim Buchanan//The Sylvia (North Carolina) Herald

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the Nov. 23 edition of The Sylvia Herald and is reprinted with permission.

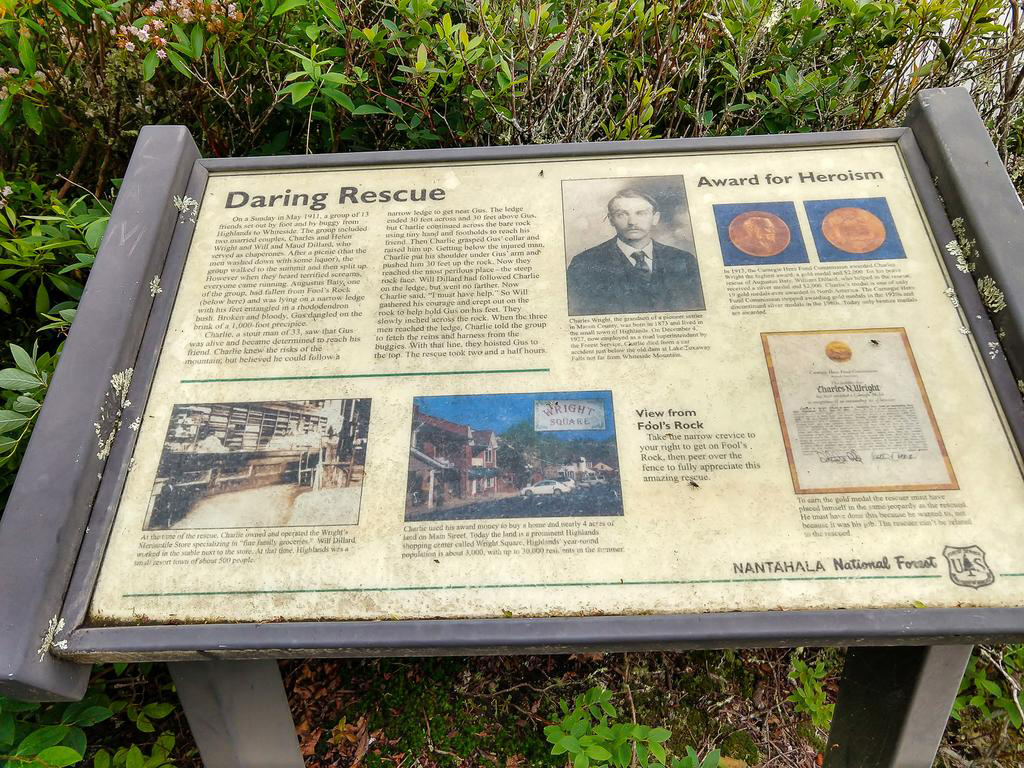

It’s been more than 110 years since news hit Jackson County that a couple of mountain men’s heroics on Whiteside Mountain had earned them recognition from the prestigious Carnegie Hero Fund.

The incident that sparked the honor had occurred a couple of years before, in May of 1911. It might have become one of those tales only handed down by local families or perhaps lost in time altogether were it not for something of a lobbying campaign to give the rescuers their proper recognition.

Rolling the clock back a bit further, Andrew Carnegie sold Carnegie Steel to J.P. Morgan in 1901. That netted Carnegie the tidy sum of nearly one-quarter of a billion dollars’ worth of bonds. Three years later the Harwick Mine disaster occurred in Cheswick, Pennsylvania, an explosion claiming 179 miners and two aid workers, Daniel Lyle and Selwyn Taylor, who were overcome by fumes while looking for survivors. The incident haunted Carnegie – “I can’t get those widows and children of the mine out of my head” – and he gave $40,000 to the Harwick relief committee and presented two gold medals to Lyle and Tyler.

That was the birth of the Hero Fund, which had its inaugural class in 1905.

The Rev. G.W. Belk heard of the Whiteside rescuers and thought they’d be fine recipients. He penned an article that ran in a number of newspapers across the state recounting their saga.

He opened his tome with his amazement upon seeing Whiteside himself, taken with its imposing rise and sheer cliffs, before recounting the tale.

“About three months ago, a party of sight-seers from Highlands set out for Whiteside Mountain. The company was composed of Mr. and Mrs. Charles N. Wright, Mr. and Mrs. {William L.) Dillard, and Misses Martha Heacock, Eliza Peek and Irena Edwards; Messrs. Frank Cabe, Hatley McCall, Sam Reese, Barney Wilson, Gus Baty and Jean Potts. Just 13 in all. On reaching the summit the company soon became divided, some going to the highest point, some to the ‘Lion’s Tongue’ or ‘Fool’s Rock,’ while Mr. and Mrs. Wright, Miss Heacock and Mr. McCall went on some 200 yards farther to the north. Suddenly the top of the mountain was ringing with wild screams. Mr. Wright rushed rapidly to the scene. All was confusion. The women were running to and from, almost frantic. Mr. Baty and some of the others had been out on the rock, viewing the scenes with a glass, when, in a moment of dizziness, he made a false step and slipped from the projecting rock and shot like an arrow down the cliff. Just then one of the girls fainted.”

Wright climbed out on the rock and saw Baty had fallen some distance but had been caught by the last piece of vegetation, a scrub rhododendron, and was dangling over a sheer drop of around 1,800 feet. Belk wrote, “No man in the country knows Whiteside Mountain better than Charlie Wright, and no one better knew the risk of attempting to reach Baty.”

He asked Dillard to accompany him on a rescue attempt, to which Dillard agreed. The two navigated a ledge to get within 30-40 feet of Baty. Facing a sheer cliff, Dillard turned back, while Wright went on, his only purchase being small crevasses in the cliff face to a position about 20 feet above Baty. Somehow he managed to maneuver down to the badly injured Baty, who was severely bruised in addition to having had a large stick pierce his head behind the ear.

And there the two were, 2,000 feet of air below them and 60 feet of steep slope above.

Wright pulled Baty up by the collar and began inching his way up the rock face. “To get out himself would seem almost impossible. But to climb that rock with a man half killed, would be little less than a miracle,” Belk wrote.

Wright called out to Dillard, saying he if couldn’t help he needed to send for help. Realizing the two men were in mortal peril, “Dillard took on new courage” recounting to Belk “We held Baty on his feet, one on each side, dragging and pushing him little by little — moving his feet along with our feet, and holding on, I don’t know how, till we reached the ledge where the rock was not so steep. Here we rested, till the lines and halters from the buggies were brought, and we tied them around Mr. Baty and pulled him to the top.”

Belk concluded his report thusly: “No report of this incident has been given to the papers. A man must see the mountain to be fully impressed with the degree of heroic nerve necessary to do such a deed. A gentleman who knew all the facts, said to me, ‘Charlie Wright is the only man in this county, in my judgment, who has the nerve and the courage even to have attempted to rescue Gus Baty from the edge of that cliff. And after seeing the place I am of the same opinion. If any man ever deserved the hero medal, Charlie Wright is that man. And next to him, W.M. Dillard. These men told me that no sum of money could tempt them to undertake it again. If Mr. Carnegie ever gave a medal to men who deserved it, let him give medals to Charlie Wright and, W.M. Dillard.”

Over the years details of the story changed in varying accounts, including Baty falling when showing off for the girls in the outing to whiskey being involved. In a 2015 article in the Herald Gary Carden recounted “a number of mythical tales emerged about the incident, and Gus was often asked about the bottle of whiskey in his pocket. Gus said that the bottle broke in his fall. He also noted that he never touched another drop of whiskey. Instead, he became a gifted carpenter and his handiwork can still be seen in a number of houses in Highlands. Gus once told an interviewer, ‘I built good houses and I wish folks would remember that instead of the fact that I fell off Whiteside Mountain.’”

The Jackson County Journal reported the Hero awards on Nov. 13, 1913. Wright received $2,000 and a gold medal, Dillard a silver medal and $2,000.

Rev. Belk’s account almost certainly spurred that recognition. One can imagine he was a very persuasive man in the pulpit as well.